THE GREAT ANIMAL ORCHESTRA VISION

The sounds of our mothers’ heartbeats were the first sounds we heard. That’s likely the reason why we respond so well to rhythm -- why we like the beat, the bass, the underlying funk.

The sounds of the wild were the first sounds we ever heard as a species. While these sounds had meaning -- mostly related to mating and survival -- the wild symphonies that played out in the jungles, forests, deserts, swamps, savannahs, and other landscapes, were the first forms of music to our ears. This sound isn’t just beautiful to hear, it is beautiful to see, smell, taste, feel -- experience in its entirety.

Bernie Krause has devoted his life to the study and celebration of the beauty of sound in nature. His work is epic and highly respected in the world of sound design and audio engineering.

Krause and composer Richard Blackford were recently commissioned by the Cheltenham Music Festival in the UK, to create a suite for orchestra based on “The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World's Wild Places

There was a moment, back in 1983, when Krause was on an sound expedition in Kenya, when he was struck with the epiphany that blossomed into a wild sonic symphony, which formed the foundation for The Great Animal Orchestra piece.

Here is the excerpt from The Great Animal Orchestra (Little Brown, 2012) that relives that moment -- with vivid recollections of the sounds and visions deep in the wilds of Africa. From Chapter 4: Biophony – the Proto-Orchestra:

After midnight at Governors’ Camp in the Masai Mara, I set up my gear and began to collect extremely rich natural sound from a nearby old-growth forest—one typical of what early humans might have encountered.

After the camp’s generators had been shut down and the staff retired, it finally became quiet, except for the forest ambience itself….The magnificence of creature voices was enhanced, no doubt, by my total exhaustion. I felt like I was hallucinating. The sonorities shifted like waves of Möbius strips wafting by in the still evening air, anchored by the throbbing rhythm of the insects.

My mics were mounted on a tripod just outside my tent by the river, where I had settled into my sleeping bag wearing a set of earphones. I didn’t care if my batteries went dead—I was hoping to lull myself to sleep with the gentle predawn atmosphere as background.

It was in that semifloating state—that transition between the blissful suspension of awareness and the depths of total unconsciousness—that I first encountered the transparent weave of creature voices, not only as a choir, but coming to me as a cohesive sonic event.

No longer a cacophony it became a partitioned collection of vocal organisms—a highly orchestrated acoustic arrangement of insects, spotted hyenas, eagle-owls, African wood-owls, elephants, tree hyrax, distant lions, and several knots of tree frogs and toads.

Every distinct voice seemed to fit within its own acoustic bandwidth—each one so carefully placed that it reminded me of Mozart’s elegantly structured Symphony no. 41 in C Major, K. 551. Woody Allen once remarked that the Forty-first proved the existence of God. That night, listening to the most vivid soundscape experience I’d had to that moment, I came as close as I would ever come to said revelation…

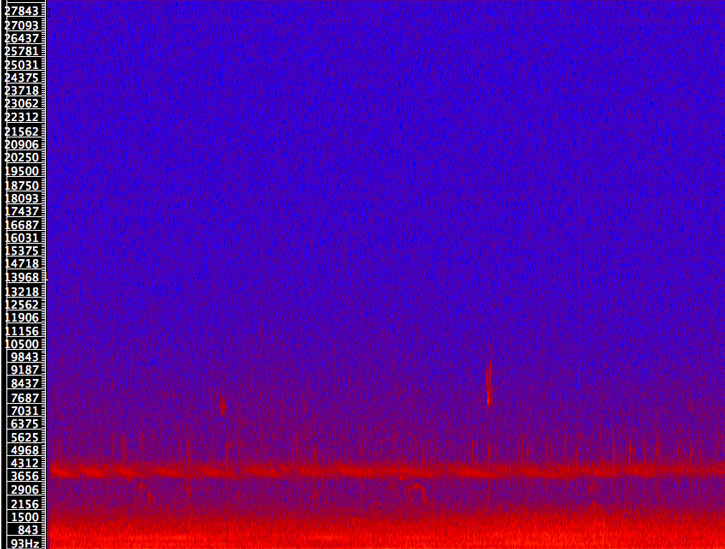

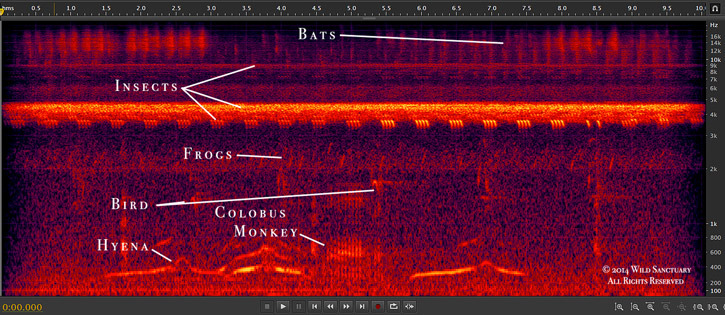

When I arrived back at the lab in San Francisco, one of my first tasks was to transform the recorded samples into spectrograms—graphic displays of sound showing time and frequency, where time is represented from left to right on the x-axis, and frequency from low to high on the y-axis. When I listened to playbacks of my audiotapes and looked at the related spectrograms, my heart began to race with anticipation.

Just as black-and-white photographic images gradually appear on photo paper during the development process, unmistakably clear patterns materialized from the printer representing the audio sequences I had recorded.

As the images slowly emerged, the überstructure of the soundscape plainly showed distinctive shapes not unlike modern forms of musical notation—the bat was vocalizing in the highest frequency range, insects in the middle, colobus and hyenas… at the lowest end of the biophonic score. And each representation was unique.

The bat was echolocating, sending out brief, high-frequency pulses of sound shown as two sharp lines in the upper-right-hand side of Figure 5. The colobus monkey, the “soloist” of the moment, sounded like a windup toy—a series of progressively slower grinding sounds followed by high, breathless screams. The tracery of its voice is illustrated midway across the page, beginning at the left-hand side.

Once it completes a phrase, the hyrax repeats its vocalization all over again. A distant hyena found a location in the forest that resonated like an echo chamber—probably a water hole—and its voice reverberated, hanging over the soundscape in a different way than the other animals.

Before I printed those first spectrograms on my return from Kenya, I had considered natural sound to be a chaotic random expression….But after Kenya, as I began to look more closely and found new acoustic software tools to work with, the patterns suggesting musical structures in the natural soundscape became too obvious to dismiss… Now for the first time, certain patterns with the acoustic organization became clear.

While Krause is primarily focused on the audio aspect, we marvel at the visual aspect as well. From jungle images, to the spectrograms created by wild sounds, this is what beautiful sound looks like. And now, close your eyes and listen to the beauty of what nature sounds like.

Check out one clip, and another, from The Great Animal Orchestra.

For more information, visit Bernie Krause’s Wild Sanctuary.

And watch Bernie Krause’s fascinating TED Global 2013 talk.

Bernie Krause recently served as one of the judges for the Most Beautiful Sound in the World Competition.

Image: Courtesy ofStay on Beat. Sound wave.

Image: Courtesy ofStay on Beat. Sound wave.

Read more about Beautiful Sound Visions, as they relate toArts/Design,Nature/Science,Food/Drink, Place/Time,Mind/Body, Soul/Impact, including 10 New Books on Sound & Vision, in our posts throughout this week.

Enter this week’sBN Competition. Our theme this week is Beautiful Sound Visions. Send in your images and ideas. Deadline is 01.19.14.

Photo: Courtesy ofInterActiveMediaSW.

Also, check out our special competition: The Most Beautiful Sound in the World! We are thrilled about this effort, together with SoundCloud and The Sound Agency. The Winner was announced today at 12:00 p.m EST. Click here to see and hear the winning entry.

Photo Credits

1) Photo: Ramesh NG. Lion from Nehru Zoo HYD.

2) Photo: Courtesy of Dark Mountain. St. Vincent Head Shot.

3) Photo: Nick Nichols. Bernie Krause at Dian Fossey’s mountain gorilla camp in Karisoke, Rwanda.

4) Photo: Courtesy of Governor’s Camp. View of the savannah from Governor’s Camp.

5) Photo: Courtesy of Two and a Half Backpacks. Kings of the Jungle.

6) Photo: Alex Berger. African watering hole at sunset.

7) Photo: Courtesy of University of Exeter Africa. Sunset on Masai Mara.

8) Photo: Gopal Vijayaraghavan. Colobus Monkey.

9) Photo: Graeme Guy. Tree Frog.

10) Photo: Courtesy of Arbsonics. Bird and Cricket soundscape frequencies graph.

11) Photo: Courtesy of Earthguide. Bat hunting.

12) Photo: evelyn.alpert. Tree Hyrax.

13) Photo: Courtesy of Wild Sanctuary. Spectrogram of animal sound

14) Image: Courtesy of Bay Back Books.

15) Image: Courtesy ofStay on Beat. Sound wave.

16) Photo: Courtesy of InterActiveMediaSW.